Explore fabulous Fermanagh in two fun tours

“Enniskillen is Ireland’s only island town,” lilts Bryan Gallagher in his border-county brogue. “It’s surrounded by water, with five bridges to get on and off.”

We’re bobbing on that water just off Enniskillen Castle Museum Jetty, gazing back up at the castle originally built by the Maguires in the 15th century, and the town that rises behind it today.

Enniskillen Castle

Those bridges are far from the only way to get off the island. Located roughly midway along Lough Erne’s many kilometres of waterway, Enniskillen is a buzzing hub for water-based adventures, from pleasure cruising to kayaking, and from open-water swimming to fresh-water fishing.

You can hug the shoreline on an Island Discovery Tour in a fully electric passenger vessel, complete with outdoor decking and indoor lounge, or hydro bike under those bridges on your own two-legged steam.

I’m setting out this afternoon to visit the ancient monastic site of Devenish Island in Erne Water Taxi’s comfortable eight-seater, with a cheerful Basque couple as my companions and a natural-born storyteller as our tour guide.

19th century bridge, Enniskillen

Barry Flanagan, Erne Water Taxi

“In the 1600s,” Bryan invites us to imagine, “this place was completely covered in thick vegetation and trees, impenetrable in places. There were wild bears, boars, wolves and – most dangerous of all – people. So, the fastest and safest way to travel was by water.

“This was their main road, and every Norman, planter, person, pig, goods, everything travelled by water. So it was a brilliant business move by the Maguires to put their castle here at the narrowest point of the waterway: they effectively had a toll bridge, and they had a say over everybody who came up and down the lough.”

Devenish Island

We slip now under the island’s oldest bridge, hand-built in 1885 and tilt our heads hillside towards Enniskillen Royal School, formerly Portora Royal School whose alumni include writers Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett.

I’m happy to sit back, digest all that I’ve seen and heard, and take in the soothing sights as Bryan steers the boat south towards his favourite spot in Lough Erne.

Along the way he points out magic we might otherwise miss. Like where “the trees bush way out and the branches lie down on the lough and if you’re lucky, you get to see a kingfisher along here: a small bird with an iridescent turquoise coat and brown front, flying ramrod straight, dipping in and out on the water.”

Or how, dotting the horizon as the adjoining river opens into Lough Erne Upper, those yellow buoys mark eel nets set by fishermen to catch this freshwater delicacy.

Devenish Island

As we cruise by, they put me in mind of all the distinctive flavours enjoyed here over the centuries. I’ve had a busy morning in the company of Mark Edwards, on his Saturday morning Taste of Enniskillen food tour. Mark – another Enniskillen local with a gift for the gab – presented a colourful overview of some of Fermanagh’s food heritage.

We heard of the butter so precious they buried it like treasure in the Middle Ages (you can view some millennia-old, bog-preserved butter in one of the castle’s eclectic museum galleries).

Keith McCurry, Taste of Enniskillen food tour

Katrina McCaverty enjoys the tour

Of the swan and venison roasted by Hugh “The Hospitable” Maguire for his legendary feasts, where strict table etiquette applied. (“You weren’t allowed scratch your hair in case anything fell out of it; to double dip with your fingers; or to pick your teeth with your knife,” Mark informs us.)

We learned of the 19th century Scotch Stores from where local Christmas turkeys were plucked and dispatched far and wide. And of the rare breed pigs farmed as wild today on their own private island by third-generation butcher Pat O’Doherty for his award-winning Fermanagh Black Bacon.

Scones from Rebecca’s Café, Taste of Enniskillen tour

We sampled airy scones slathered in butter and homemade jam outside Rebecca’s Café, named after the first woman to sell her own bread at the 19th-century dairy market (now restored as the smart Buttermarket craft village courtyard).

We sampled Tickety Moo Ice Cream at Ruby’s café, from Jersey cows you can visit at the Grey family’s working farm, where the happy herd avail of automated milking machines and “a big robotic brush scratching their backsides” whenever they want.

We indulged in confident contemporary cooking from young local chef-restaurateurs who have done star turns on the Great British Menu TV show: Marty McAdam of Paget Lane and Street Kitchen, and Glen Wheeler of 28 at The Hollow. And we refreshed ourselves with world-class gin made lakeside at Boatyard Distillery.

Moira Murphy and Nuala McCarron sample Tickety Moo Ice Cream

Jamielee Boyd, Street Kitchen

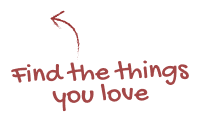

Right now, though, we are approaching this afternoon’s idyllic destination, Devenish Island, and it looks like the gods have arranged a light show for us.

Sunlight streams in high-contrast shafts between the summer shower clouds, picking out historical highlights that rise in soft grey stone from the freshly washed grass. We see a 900-year-old round tower in mint condition.

Behind it St Mary’s Augustinian priory, built in the 15th century but dissolved by Cromwell for Henry VIII in the mid-16th century. And on the foreshore, the ruins of the 12th century Teampal Mór (big church), built on the site of the original church founded by St Molaise in the 6th century.

Devenish Island

“I’m so glad you got to see it in the sunshine,” Bryan exclaims as we hop ashore, before instructing us to close our eyes and drink in the silence, broken only by the cry of birds and the rush of wind. “You can see what the attraction is,” he whispers. “I’m not a religious man but I know Devenish Island is a special place.”

Within moments the rain starts, but within seconds we’re huddled under Bryan’s enormous umbrella as he turns history inside out again.

Round Tower on Devenish Island

Stone carvings on Devenish Island

“People think that silence is why the monks settled here: for solitude to pray,” he tells us. “But once you remember that everything travelled by water, that this was the highway of their time, suddenly all of the monastic sites on the sides of islands make sense.

“Nowadays we come out here to get away from people – but these monastic sites were the motorway service stations: they wanted you to call in! And they were right in the middle of all of the action.”

Devenish Island boat jetty

At its bustling, thriving best, Bryan tells us, this small island – just two kilometres long and half that in width – would have been a noisy, densely populated place. The day would have been punctuated by the bell calling islanders to prayer or to food or to work, or warning of attack; the air full with the sounds of children playing, people cooking, working in the fields, fishing on the lake.

Bryan has been coming here since he was a child. He has a photo on his phone to prove it, taken by his father five decades ago: a brood of cousins covering the steps outside the round tower. And he has centuries worth of stories to share about every inch of this blessed island.

High Cross on Devenish Island

Barry Flanagan

Of how that stone high cross would once have been “painted the most vibrant colours they could find” as a teaching tool for children. Of local beliefs about the curative properties of the island’s bullán stone: a smooth stone indented with a natural depression believed to cure anything from “a bad back or a bad knee to bad thoughts or a bad husband or wife”.

And of how Ireland’s special strain of Celtic Christianity allowed various ways of understanding the world to co-exist, so that “even if we don’t believe in cures and the curative properties of the land, we don’t disbelieve it – and we definitely do not disrespect it”.

Ruins of the Teampal Mór (big church), Devenish Island

Bryan is still coming here with his father, now 88. They like to cruise out on a summer’s evening to float on the water, gazing up at the island and back out at the lake’s shoreline, unchanged since the monks and the Vikings and the Maguires and the Normans and the planters sailed into these waters.

“You can see why we’re utterly in love with it,” he says.

Devenish Island

I can. But more than that: thanks to Bryan’s and Mark’s vivid retelling, I can see beyond the fluid beauty in today’s ever-changing light and into the colourful, action-packed past of these history-rich islands and waterways. And that’s a gift.